To obey a rule, to make a report, to give an order, to play a game of chess, are customs.

It is ...easy to be certain. One has only to be sufficiently vague.

Leading a human life is a full-time occupation, to which everyone devotes decades of intense concern.

A philosophy has no private store of knowledge or methods for attaining truth, so it has no private access to good. As it accepts knowledge and principles from those competent in science and inquiry, it accepts the goods that are diffused in human experience. It has no Mosaic or Pauline authority of revelation entrusted to it. But it has the authority of intelligence, of criticism of these common and natural goods.

There are many kinds of gods. Therefore there are many kinds of men.

It is from the Bible that man has learned cruelty, rapine, and murder; for the belief of a cruel God makes a cruel man.

I was still blind, but twinkling stars did dance Throughout my being's limitless expanse, Nothing had yet drawn close, only at distant stages I found myself, a mere suggestion sensed in past and future ages.

This opinion... appears to be ancient... that the one, excess and defect, are the principles of things... It is not... probable that there are more than three principles... [E]ssence is one certain genus of being: so that principles will differ from each other in prior and posterior alone, but not in genus, for in one genus there is always one contrariety, and all contrarieties appear to be referred to one. That there is neither one element, therefore, nor more than two or three, is evident.

Now, to-day, this moment, is our chance to choose the right side. God is holding back to give us that chance. It will not last for ever. We must take it or leave it.

I may as well say at once that I do not distinguish between inference and deduction. What is called induction appears to me to be either disguised deduction or a mere method of making plausible guesses.

The Son of man shall be betrayed into the hands of men: And they shall kill him, and the third day he shall be raised again.

Nature consists of the elements given by the senses. Primitive man first takes out of them certain complexes of these elements that present themselves with a certain stability and are most important to him. The first and oldest words are names for "things". ... The sensations are no "symbols of things". On the contrary the "thing" is a mental symbol for a sensation-complex of relative stability. Not the things, the bodies, but colours, sounds, pressures, times (what we usually call sensations) are the true elements of the world.

A city that outdistances Man's walking powers is a trap for Man. It threatens to become a prison from which he cannot escape unless he has mechanical means of transport, the thoroughfares for carrying these, and the purchasing power for commanding the use of artificial means of communication.

A whole dimension of human activity and passivity has been de-eroticized. The environment from which the individual could obtain pleasure-which he could cathect as gratifying almost as an extended zone of the body-has been rigidly reduced. Consequently, the "universe" of libidinous cathexis is likewise reduced. The effect is a localization and contraction of libido, the reduction of erotic to sexual experience and satisfaction.

People are entirely too disbelieving of coincidence. They are far too ready to dismiss it and to build arcane structures of extremely rickety substance in order to avoid it. I, on the other hand, see coincidence everywhere as an inevitable consequence of the laws of probability, according to which having no unusual coincidence is far more unusual than any coincidence could possibly be.

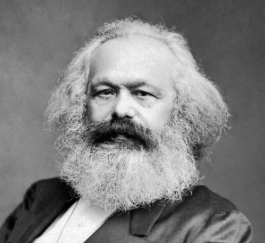

Gold is now money with reference to all other commodities only because it was previously, with reference to them, a simple commodity.

Today, tattoos lack symbolic power. All they do is point toward the uniqueness of the bearer. The body is neither a ritual stage nor a surface of projection; rather, it is an advertising space.

If God stops a man on the road, and calls him with a revelation and sends him armed with divine authority among men, they say to him; from whom dost thou come? He answers: from God. But now God cannot help his messenger physically like a king, who gives him soldiers or policemen, or his ring or his signature, which is known to all; in short, God cannot help men by providing them with physical certainty that an Apostle is an Apostle-which would, moreover, be nonsense. Even miracles, if the Apostle has that gift, give no physical certainty; for the miracle is the object of faith.

Agriculture is now a motorized food industry, the same thing in its essence as the production of corpses in the gas chambers and the extermination camps, the same thing as blockades and the reduction of countries to famine, the same thing as the manufacture of hydrogen bombs.

Primitivism has become the vulgar cliche of much modern art and speculation.

The owl of Minerva first begins her flight with the onset of dusk.

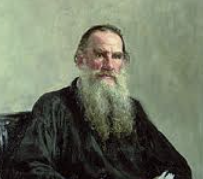

Saying that what we call our "selves" consist only of our bodies and that reason, soul, and love arise only from the body, is like saying that what we call our body is equivalent to the food that feeds the body. It is true that my body is only made up of digested food and that my body would not exist without food, but my body is not the same as food. Food is what the body needs for life, but it is not the body itself. The same thing is true of my soul. It is true that without my body there would not be that which I call my soul, but my soul is not my body. The soul may need the body, but the body is not the soul.

For he who is unmusical is a child in music; he who is without letters is a child in learning; he who is untaught, is a child in life.

The critique of the highest values hitherto does not simply refute them or declare them invalid. It is rather a matter of displaying their origins as impositions which must affirm precisely what ought to be negated by the values established.

It is often asserted that discussion is only possible between people who have a common language and accept common basic assumptions. I think that this is a mistake. All that is needed is a readiness to learn from one's partner in the discussion, which includes a genuine wish to understand what he intends to say. If this readiness is there, the discussion will be the more fruitful the more the partner's backgrounds differ.

For those who want 'to change life", 'to reinvent love,' God is nothing but a hindrance.

The inscrutable wisdom through which we exist is not less worthy of veneration in respect to what it denies us than in respect to what it has granted.

Nature is a structure of evolving processes. The reality is the process.

I entirely agree with you, as to the ill tendency of the affected doubts of some philosophers, and fantastical conceit of others. I am even so far gone of late in this way of think, that I have quitted several of the sublime notions I had got in their schools for vulgar opinions. And I give it you on my word, since this revolt from metaphysical notions to the plain dictates of nature and common sense, I find my understanding strangely enlightened, so that I can now easily comprehend a great many thing which before were all mystery and riddle.

Man starts over again everyday, in spite of all he knows, against all he knows.

Ridden with conflicts and lacking the industrial base of communism and nazism, Islamism is nowhere near a danger of the magnitude of those that were faced down in the 20th century.

But the man is a humbug - a vulgar, shallow, self-satisfied mind, absolutely inaccessible to the complexities and delicacies of the real world. He has the journalist's air of being a specialist in everything, of taking in all points of view and being always on the side of the angels: he merely annoys a reader who has the least experience of knowing things, of what knowing is like. There is not two pence worth of real thought or real nobility in him. But he isn't dull.

One of the problems... both on the left and the right is that the... individual autonomy protected by liberalism tends to take more and more extreme versions... and... becomes self-undermining.

As much in vain, perhaps, will they search ancient history for examples of the modern Slave-Trade. Too many nations enslaved the prisoners they took in war. But to go to nations with whom there is no war, who have no way provoked, without farther design of conquest, purely to catch inoffensive people, like wild beasts, for slaves, is an hight of outrage against Humanity and Justice, that seems left by Heathen nations to be practised by pretended Christians. How shameful are all attempts to colour and excuse it!

What chiefly diverts the men of democracies from lofty ambition is not the scantiness of their fortunes, but the vehemence of the exertions they daily make to improve them.

You want to know whether I can make a long speech, such as you are in the habit of hearing; but that is not my way. Socrates speaking to Alcibiades

...a monarchy is a thing perfectly susceptible of reform; perfectly susceptible of a balance of power; and that, when reformed and balanced, for a great country, it is the best of all governments. The example of our country might have led France, as it has led him, to perceive that monarchy is not only reconcilable to liberty, but that it may be rendered a great and stable security to its perpetual enjoyment.

Architecture is a way for power to achieve eloquence through form.

When I endeavour to examine my own conduct, when I endeavour to pass sentence upon it, and either to approve or condemn it, it is evident that, in all such cases, I divide myself, as it were, into two persons; and that I, the examiner and judge, represent a different character from that other I, the person whose conduct is examined into and judged of.

"And your education! Is not that also social, and determined by the social conditions under which you educate, by the intervention, direct or indirect, of society, by means of schools, etc.? The Communists have not invented the intervention of society in education; they do but seek to alter the character of that intervention, and to rescue education from the influence of the ruling class."

Treat your friend as if he might become an enemy.

One cannot ignore half of life for the purposes of science, and then claim that the results of science give a full and adequate picture of the meaning of life. All discussions of 'life' which begin with a description of man's place on a speck of matter in space, in an endless evolutionary scale, are bound to be half-measures, because they leave out most of the experiences which are important to use as human beings.

Superstition is the religion of feeble minds.

The circulation of commodities is the original precondition of the circulation of money.

It was a purely Christian satisfaction to me that if ordinarily there was no one else there was one who in action tried a little to do the doctrine about loving the neighbor, alas, one who precisely by his act also received a frightful into what an illusion Christendom is and indeed, particularly later, also into how the common people let themselves be seduced by wretched journalists, whose striving and fighting for equality can only lead, if it leads to anything, since it is in the service of the lie, to making the elite, in self-defense, proud of their aloofness from the common man, and the common man brazen in his rudeness.

An aphorism? Fire without flames. Understandable that no one tries to warm himself at it.

All traditional logic habitually assumes that precise symbols are being employed. It is therefore not applicable to this terrestial life but only to an imagined celestial existence... logic takes us nearer to heaven than other studies.

Talk of mysteries! - Think of our life in nature, - daily to be shown matter, to come in contact with it, - rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! The solid earth! the actual world! the common sense! Contact! Contact! Who are we? where are we?

That which is good for the enemy harms you, and that which is good for you harms the enemy.

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia