Liberalism has been very severely threatened in recent years. It's been threatened from a number of sources. So internationally you have two great powers, Russia and China, that are definitely not liberal polities, that have expansive ambitions... As Vladimir Putin said... in an iterview with the FT in 2019 "Liberalism is an obsolete doctrine." But the threat... also comes from other places. ...You have the rise of a populist nationalist right in many countries. This is Viktor Orbán in Hungary. This is Narendra Modi in India, Donald Trump in the United States, ...Marine Le Pen in France. All of them criticizing liberalism precisely for the tolerance that it permits and tries to deal with, in diverse and increasingly ethnically and racially diverse countries.

Happiness is not achieved by the conscious pursuit of happiness; it is generally the by-product of other activities.

So monstrous is the making and keeping them slaves at all, abstracted from the barbarous usage they suffer, and the many evils attending the practice; as selling husbands away from wives, children from parents, and from each other, in violation of sacred and natural ties; and opening the way for adulteries, incests, and many shocking consequences, for all of which the guilty Masters must answer to the final Judge.

Headlines are icons, not literature.

His business is here, it is here that he is despised and vilified, it is here that he must carry out his undertaking.

Ever since the war began, I have felt that I could no longer go on being a pacifist, but I have hesitated to say so, because of the responsibility involved. If I were young enough to fight myself, I should do so, but it is more difficult to urge others. Now, however, I feel that I ought to announce that I have changed my mind.

Ten thousand do not turn the scale against a single man of worth.

People talk, indeed, of a "primitive mentality", as, for example, to-day that of the inferior races, and in days gone by that of humanity in general, at whose door the responsibility for superstition should be laid.

The best friend is he that, when he wishes a person's good, wishes it for that person's own sake.

We speak not strictly and philosophically when we talk of the combat of passion and of reason. Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.

Faith consists in believing what reason cannot.

The concept of freedom, as the Philosophy of Right has shown, follows the pattern of free ownership. As a result, the history of the world that Hegel looks out upon exalts and enshrines the history of the middle-class, which based itself on this pattern. There is a stark truth in Hegel's strangely certain announcement that history has reached its end. But it announces the funeral of a class, not of history.

In different hours, a man represents each of several of his ancestors, as if there were seven or eight of us rolled up in each man's skin, - seven or eight ancestors at least, - and they constitute the variety of notes for that new piece of music which his life is.

We do not "have" a body; rather, we "are" bodily.

No man can justly censure or condemn another, because indeed no man truly knows another.

To Xeniades, who had purchased Diogenes at the slave market, he said, "Come, see that you obey orders."

Men became scientific because they expected law in Nature; and they expected law in Nature because they believed in a Legislator.

I would advise no one to send his child where the Holy Scriptures are not supreme. Every institution that does not unceasingly pursue the study of God's word becomes corrupt. Because of this we can see what kind of people they become in the universities and what they are like now. Nobody is to blame for this except the pope, the bishops, and the prelates, who are all charged with training young people. The universities only ought to turn out men who are experts in the Holy Scriptures, men who can become bishops and priests, and stand in the front line against heretics, the devil, and all the world. But where do you find that? I greatly fear that the universities, unless they teach the Holy Scriptures diligently and impress them on the young students, are wide gates to hell.

Once he saw the officials of a temple leading away some one who had stolen a bowl belonging to the treasurers, and said, "The great thieves are leading away the little thief."

There's no objective morality, but that's not the real point. It's not the point that morality has to somehow be a stone, or something that can be touched.

The options that are available to choose are determined to a point, and this is the objective aspect of morality, ethics, goodness, fairness, justice.

The subjective aspect can still remain subjective, but that doesn't mean goodness is relative.....at all. The measure of a man is a man.

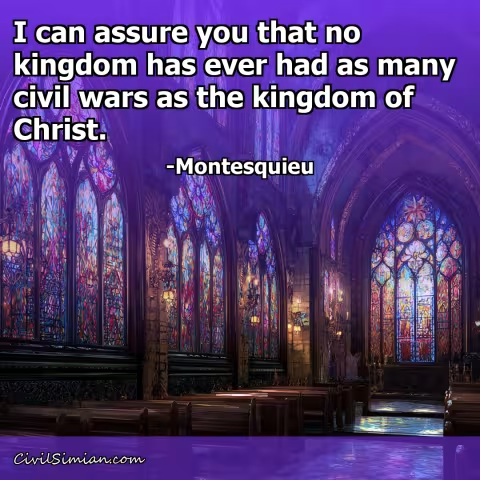

I have seen something of the project of M. de St. Pierre, for maintaining a perpetual peace in Europe. I am reminded of a device in a cemetery, with the words: Pax perpetua; for the dead do not fight any longer: but the living are of another humor; and the most powerful do not respect tribunals at all. Letter 11 to Grimarest: Passages Concerning the Abbe de St. Pierre's 'Project for Perpetual Peace' (June 1712).

All ages before ours believed in gods in some form or other. Only an unparalleled impoverishment in symbolism could enable us to rediscover the gods as psychic factors, which is to say, as archetypes of the unconscious. No doubt this discovery is hardly credible as yet.

Spinoza, for example, thought that insight into the essence of reality, into the harmonious structure of the eternal universe, necessarily awakens love for this universe. For him, ethical conduct is entirely determined by such insight into nature, just as our devotion to a person may be determined by insight into his greatness or genius. Fears and petty passions, alien to the great love of the universe, which is logos itself, will vanish, according to Spinoza, once our understanding of reality is deep enough.

The ancient philosophers... all of them assert that the elements, and those things which are called by them principles, are contraries, though they establish them without reason, as if they were compelled to assert this by truth itself. They differ, however... that some of them assume prior, and others posterior principles; and some of them things more known according to reason, but others such as are more known according to sense: for some establish the hot and the cold, others the moist and the dry, others the odd and the even, and others strife and friendship, as the causes of generation. ...in a certain respect they assert the same things, and speak differently from each other. They assert different things... but the same things, so far as they speak analogously. For they assume principles from the same co-ordination; since, of contraries, some contain, and others are contained.

Happy is the one in whom there is true sorrow over his sin, so that the extreme unimportance to him of everything else is only the negative expression of the confirmation that one thing is unconditionally important to him, so that the unconditional unimportance to him of everything else is a deadly sickness that still is very far from being a sickness unto death but is precisely unto life, because the life is in this, that one thing is unconditionally important to him: to find forgiveness.

The struggle to end sexist oppression that focuses on destroying the cultural basis for such domination strengthens other liberation struggles. Individuals who fight for the eradication of sexism without struggles to end racism or classism undermine their own efforts. Individuals who fight for the eradication of racism or classism while supporting sexist oppression are helping to maintain the cultural basis of all forms of group oppression.

Capitalist production does not exist at all without foreign commerce.

[In cloning,] the Father and the Mother have disappeared, not in the service of an aleatory liberty of the subject, but in the service of a matrix called code.

How great is the path proper to the Sage! Like overflowing water, it sends forth and nourishes all things, and rises up to the height of heaven. All-complete is its greatness! It embraces the three hundred rules of ceremony, and the three thousand rules of demeanor. It waits for the proper man, and then it is trodden. Hence it is said, "Only by perfect virtue can the perfect path, in all its courses, be made a fact."

The real significance of the Russell paradox, from the standpoint of the modal-logic picture, is this: it shows that no concrete structure can be a standard model for the naive conception of the totality of all sets; for any concrete structure has a possible extension that contains more 'sets'. (If we identify sets with the points that represent them in the various possible concrete structures, we might say: it is not possible for all possible sets to exist in any one world!) Yet set theory does not become impossible. Rather, set theory becomes the study of what must hold in, e.g. any standard model for Zermelo set theory.

Politics is a science. You can demonstrate that you are right and that others are wrong.

The world must be romanticized. In this way the originary meaning may be found again.

It is sublime as night and a breathless ocean. It contains every religious sentiment, all the grand ethics, which visit in turn each noble poetic mind .... It is of no use to put away the book if I trust myself in the woods or in a boat upon the pond. Nature makes a Brahmin of me presently: eternal compensation, unfathomable power, unbroken silence .... This is her creed. Peace, she saith to me, and purity and absolute abandonment - these panaceas expiate all sin and bring you to the beatitude of the Eight Gods.

The Bible is literature, not dogma.

I have been merely oppressed by the weariness and tedium and vanity of things lately: nothing stirs me, nothing seems worth doing or worth having done: the only thing that I strongly feel worth while would be to murder as many people as possible so as to diminish the amount of consciousness in the world. These times have to be lived through: there is nothing to be done with them.

It requires twenty years for a man to rise from the vegetable state in which he is within his mother's womb, and from the pure animal state which is the lot of his early childhood, to the state when the maturity of reason begins to appear. It has required thirty centuries to learn a little about his structure. It would need eternity to learn something about his soul. It takes an instant to kill him.

The WTO-related events in Seattle created the first experience of a rainbow politics-a successful pluralistic politics, without the working of a master mind, but with the currents and beauty that come out of free thinking. In the new politics, people have different ways of talking, but I feel the core will be living democracy and living economies, and that it will include both taking personal responsibility to make change and being part of national and international movements for change.

To make an end of all things on Earth, and our Planetical System of the World, he (God) need but put out the Sun.

All sources of energy upon which industry depends are wasted when they are employed; and industry is expending them at a continually increasing rate. Already coal has been largely replaced by oil, and oil is being used up so fast that East and West alike conceive it necessary to their own prosperity to destroy the industry of the other. And what is true of oil is equally true of other natural resources. Every day, many square miles of forest are turned into newspaper, but there is no known process by which newspaper can be turned into forest. You will say that this need not worry us, since newspapers will be replaced by radio, but radio requires electricity, electricity requires power, and power depends upon raw materials.

In the world of today can there be peace anywhere until there is peace everywhere?

It seems clear to me that marriage ought to be constituted by children, and relations not involving children ought to be ignored by the law and treated as indifferent by public opinion. It is only through children that relations cease to be a purely private matter.

Even if a civil society were to be dissolved by the consent of all its members (e.g., if a people inhabiting an island decided to separate and disperse throughout the world), the last murderer remaining in prison would first have to be executed, so that each has done to him what his deeds deserve and blood guilt does not cling to the people for not having insisted upon this punishment; for otherwise the people can be regarded as collaborators in his public violation of justice.

Just you think first, and don't bother to speak afterward, either.

Just as it sometimes happens that deformed offspring are produced by deformed parents, and sometimes not, so the offspring produced by a female are sometimes female, sometimes not, but male, because the female is as it were a deformed male.

The mentality of mankind and the language of mankind created each other. If we like to assume the rise of language as a given fact, then it is not going too far to say that the souls of men are the gift from language to mankind. The account of the sixth day should be written: He gave them speech, and they became souls.

Anyone can hold the helm when the sea is calm.

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia