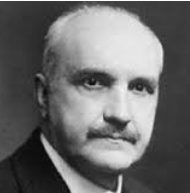

George Santayana — Skepticism, Spirit, and the Life of Reason (1863–1952)

George Santayana was a philosopher who refused to hurry. Suspicious of moral fervor, ideological certainty, and philosophical systems, he cultivated distance — from nations, from movements, and even from belief itself. A naturalist without reductionism and a skeptic without despair, Santayana treated philosophy as a reflective art: a way of understanding how humans create meaning in a universe that offers none by default.

A Spaniard in America

Born in Madrid and raised partly in Boston, Santayana lived between cultures from the start. Though he spent decades teaching at Harvard, he never felt entirely American — nor did he wish to. Detachment, for Santayana, was not alienation but freedom.

He studied under William James and Josiah Royce, absorbing pragmatism and idealism while quietly resisting both. Santayana admired James’s psychological insight but rejected the idea that truth is made true by usefulness. Reality, he believed, does not bend to human needs.

“I do not believe in believing.”

Naturalism Without Naïveté

Santayana was a thoroughgoing naturalist. The universe, he held, is governed by material processes indifferent to human hopes. Mind, culture, and value emerge from nature but do not control it.

Yet his naturalism was never crude. He rejected the idea that reducing everything to matter explains away meaning. On the contrary, meanings are real — just not fundamental. They belong to the life of spirit, not to the structure of the cosmos.

“The universe is not morally significant; but man is.”

The Life of Reason

Santayana’s major philosophical work, The Life of Reason, traces how rationality emerges from instinct, habit, and imagination. Reason is not a transcendent faculty; it is a refined form of animal intelligence.

Its function is not to discover eternal truths, but to organize experience in ways that promote harmony, clarity, and fulfillment. Reason grows slowly, historically, through culture, art, religion, and science.

“Reason is simply the art of attending to experience.”

Skepticism and Animal Faith

Santayana accepted radical skepticism in theory. Absolute certainty, he argued, is unattainable. All knowledge rests on assumptions that cannot be logically justified.

Yet humans live anyway. We trust memory, perception, and inference not because they are proven, but because life requires it. Santayana called this animal faith — the instinctive confidence that makes action possible.

“Skepticism, when it is systematic, leads to animal faith.”

Religion as Poetry

Though an atheist, Santayana treated religion with unusual sympathy. Religious myths, he argued, are imaginative expressions of human ideals. They are false as literal descriptions, but true as symbols.

When taken poetically, religion can elevate life. When taken literally, it becomes superstition. Wisdom lies not in belief, but in appreciation.

Withdrawal from the Modern World

In midlife, Santayana left Harvard and eventually settled in Europe, spending his final decades in Rome. He watched the twentieth century — its wars, ideologies, and mass movements — with cultivated distance.

Progress, he believed, had been confused with noise. Civilization advances not through speed or power, but through refinement of taste and judgment.

Legacy — Elegance Against Fanaticism

Santayana left no school, no movement, and no disciples. His influence is quieter — a style of thinking marked by restraint, irony, and composure.

He remains a philosopher for those wary of certainty, unmoved by slogans, and committed to seeing the world clearly without demanding that it justify itself.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia