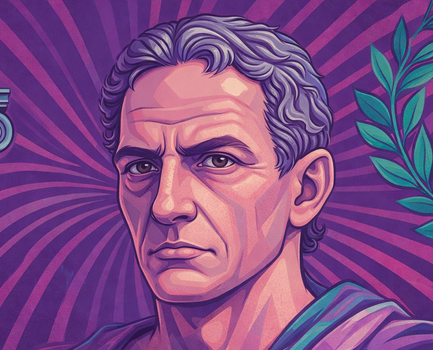

Cato the Younger — The Stoic Who Refused to Kneel to Power (95–46 BCE)

Cato the Younger was Rome’s moral immovable object. In an age of ambition, corruption, and collapsing republican ideals, he stood for an uncompromising vision of virtue, law, and personal integrity. He did not seek to win history — he sought to be worthy of it.

Born into a Republic Already in Decline

Marcus Porcius Cato, known as Cato the Younger, was born into a prominent Roman family at a time when the Republic’s institutions still stood but its spirit was eroding. From an early age, he displayed a severe temperament — disciplined, stubborn, and resistant to flattery.

Educated in Stoic philosophy, Cato absorbed the belief that virtue is the only true good and that moral duty outweighs personal safety, success, or even life itself. Philosophy for him was not reflection — it was preparation.

“I begin to speak only when I am certain what I shall say is not better left unsaid.”

Stoicism as a Way of Life

Cato lived his Stoicism publicly and relentlessly. He wore simple clothing, walked rather than rode, refused luxury, and held himself to the same laws he enforced on others. This was not performance — it was moral discipline made visible.

Stoic endurance shaped his character. Pleasure was suspect, pain was tolerable, and compromise with injustice was unacceptable. To Cato, bending the law for convenience was already the beginning of tyranny.

“Consider in silence whatever anyone says.”

The Unbending Senator

As a statesman, Cato became famous — and infamous — for his refusal to compromise. In the Roman Senate, he opposed bribery, populist demagoguery, and the accumulation of personal power. His greatest adversary was Julius Caesar, whose ambition Cato saw as a direct threat to republican liberty.

While others maneuvered for advantage, Cato insisted that the law must rule, not men. His integrity earned admiration, but also isolation. In a political culture built on deals, he spoke the language of absolutes.

“The worst ruler is one who cannot rule himself.”

Freedom Over Life Itself

When Caesar crossed the Rubicon, civil war became inevitable. Cato sided with the defenders of the Republic, even as defeat loomed. After Caesar’s victory, Cato retreated to Utica in North Africa, where he faced a final choice: submission or freedom.

Refusing to live under a ruler he regarded as illegitimate, Cato took his own life — not as an act of despair, but as a declaration. For Stoics, freedom lies in moral agency, and Cato chose to die free rather than live obedient.

“A wise man will never be a voluntary slave.”

A Symbol That Outlived Rome

Cato’s death electrified the ancient world. To his admirers, he became the embodiment of republican virtue. To his critics, he was tragically inflexible. Either way, his moral gravity was undeniable.

Later generations — from Seneca and Lucan to Renaissance republicans and Enlightenment thinkers — saw in Cato a symbol of resistance against tyranny and moral decay. He represents the question every age must face: how much is virtue worth when power demands obedience?

“I shall die, but I shall not be conquered.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia