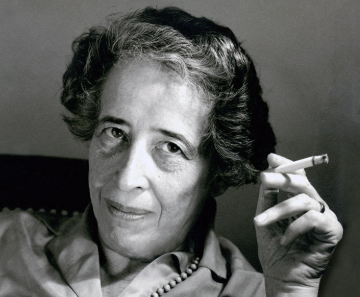

Theorist of Totalitarianism, Action, and the Banality of Evil

1906–1975

Hannah Arendt confronted the darkest moments of the twentieth century with unflinching intellectual courage. As a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany, she turned her experience of statelessness and terror into profound political theory. Her insights into totalitarianism, human action, and the nature of evil remain essential for understanding how democracies fail and what politics truly means.

From Königsberg to Exile

Born in Königsberg, the city of Immanuel Kant, Arendt showed early brilliance. She studied philosophy with Martin Heidegger, with whom she had a complex and controversial relationship, and Karl Jaspers, who became her lifelong friend and mentor. Her dissertation explored Augustine's concept of love, showing interests that would define her work: how humans relate to each other and to the world.

When Hitler rose to power, Arendt was arrested for researching antisemitism. She escaped to France, then fled again when France fell, eventually reaching America in 1941. Statelessness—the experience of being stripped of legal protections and political community—became central to her thinking about what it means to be human in the political realm.

No one has the right to obey.

The Origins of Totalitarianism — Evil Systematized

Arendt's first major work analyzed how Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia represented something unprecedented: total domination that sought to eliminate human spontaneity itself. Totalitarianism wasn't merely dictatorship but an attempt to remake reality, to make everything possible by making everything permitted, including the systematic destruction of human plurality.

She traced totalitarianism's roots to imperialism, antisemitism, and the collapse of nation-states, showing how stateless masses became vulnerable to ideologies promising certainty and belonging. The camps were laboratories where totalitarianism tested whether humans could be reduced to predictable reactions, whether individuality could be extinguished completely.

The sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.

The Human Condition — Labor, Work, Action

In The Human Condition, Arendt distinguished three fundamental human activities. Labor sustains biological life—repetitive, cyclical, necessary. Work creates the artificial world of objects that outlasts individual lives. But action—speech and deed among equals—is distinctly human, creating the space where freedom and meaning emerge.

Modern society, she argued, had elevated labor to the highest position, reducing humans to animal laborans—working, consuming, reproducing. Politics had been degraded to administration. What we lost was the public realm where citizens appear before one another, where genuine plurality allows new beginnings and unexpected possibilities.

The most radical revolutionary will become a conservative the day after the revolution.

Eichmann in Jerusalem — The Banality of Evil

Covering Adolf Eichmann's 1961 trial for The New Yorker, Arendt expected to encounter a monster. Instead, she found a mediocrity—a man who didn't think, who spoke in clichés, who performed evil acts not from ideological conviction but from careerism and inability to imagine others' perspectives. She called it "the banality of evil."

This phrase sparked enormous controversy. Critics accused her of diminishing Nazi crimes or exonerating perpetrators. But Arendt's point was more disturbing: evil doesn't require demonic motivation but merely thoughtlessness—the failure to think from another's standpoint, the replacement of judgment with bureaucratic procedure. Eichmann's evil lay precisely in his ordinariness.

The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal.

Thinking and Moral Life

Eichmann's thoughtlessness led Arendt to explore thinking's relationship to ethics. In The Life of the Mind, she argued that thinking—the internal dialogue of asking and answering questions—creates a moral safeguard. Those who think cannot commit evil comfortably because they must live with themselves, facing their conscience in that internal conversation.

Thinking doesn't provide moral rules but makes us pause before acting. It disrupts clichés and established patterns. The inability to think—not stupidity but the refusal to engage in silent dialogue with oneself—allows evil to flourish. Socrates became her model: one who couldn't do wrong because he'd have to live with a wrongdoer.

Thinking means concentrating on one thing long enough to uncover its essential nature and forge it into a meaningful word.

Natality and New Beginnings

Against totalitarianism's attempt to make everything predictable, Arendt emphasized natality—the fact that new people are constantly born, bringing unprecedented perspectives and capacities for beginning. Action, she insisted, is miraculous precisely because it interrupts deterministic chains of events, introducing genuine novelty into the world.

This wasn't naive optimism but recognition that human freedom manifests in our ability to start something new. Every birth represents potential for change. Politics, at its best, creates spaces where this natality can express itself—where people act together to shape their common world rather than being shaped by impersonal forces.

The miracle that saves the world, the realm of human affairs, from its normal, 'natural' ruin is ultimately the fact of natality, in which the faculty of action is ontologically rooted.

Freedom and the Public Realm

Arendt rejected the liberal conception of freedom as non-interference. True freedom, she argued, is positive—the capacity to act with others in public space. We're free not when left alone but when we appear before equals, engaging in speech and action that shapes our common world. Freedom requires a public realm where plurality is preserved and power emerges from collective action.

This meant democracy isn't primarily about voting or rights but about participation—citizens actively involved in self-governance. When politics becomes merely the administration of things or the protection of private interests, we lose the very space where freedom happens and where human beings can experience their full humanity.

Power corresponds to the human ability not just to act but to act in concert.

Legacy — Thinking What We Are Doing

Arendt died before completing The Life of the Mind, but her influence has only grown. She gave us vocabulary for understanding political evil, bureaucratic thoughtlessness, and the fragility of democratic institutions. Her insistence that we distinguish totalitarianism from authoritarianism, action from behavior, power from violence remains essential for political analysis.

More fundamentally, Arendt called us to think—to pause before acting, to question clichés, to imagine perspectives beyond our own. In an age of algorithmic governance, administrative politics, and polarized tribalism, her vision of the public realm as a space of appearance, speech, and collective action offers both warning and possibility. We are, she insisted, condemned to be free—responsible for the world we create together.

Education is the point at which we decide whether we love the world enough to assume responsibility for it.

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia