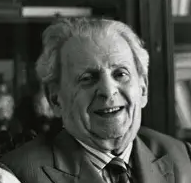

Emmanuel Levinas — The Philosopher of the Face, Responsibility, and Ethics Before Being (1906–1995)

Emmanuel Levinas turned philosophy inside out. Where most thinkers began with knowledge, being, or consciousness, Levinas began with obligation. Before we think, before we choose, before we understand the world, we are already responsible for the other person. Ethics, he insisted, is not a branch of philosophy — it is its foundation.

A Life Marked by Exile and Catastrophe

Levinas was born in Lithuania to a Jewish family steeped in religious learning. He came of age amid the collapse of empires and the rise of total war. Moving to France, he studied philosophy and became one of the first to introduce Husserl’s phenomenology and Heidegger’s thought to the French intellectual world.

World War II shattered any remaining philosophical innocence. Levinas was captured and held in a German prisoner-of-war camp, while most of his family was murdered in the Holocaust. Philosophy could no longer pretend to be neutral. Any thinking that failed to account for responsibility to others, he believed, had already failed ethically.

“After Auschwitz, one cannot think in the same way.”

Breaking with Ontology

Much of twentieth-century philosophy revolved around ontology — the study of being. Heidegger, in particular, sought the meaning of Being itself. Levinas found this project dangerous. When philosophy prioritizes Being, individuals risk becoming mere instances, absorbed into systems, histories, or destinies.

Levinas proposed a radical reversal: ethics comes before ontology. Our first philosophical encounter is not with Being, but with another person who demands something from us. Before we ask “What is?” we are already asked, “What must you do for me?”

“Ethics is first philosophy.”

The Face of the Other

Levinas’s most famous concept is the face. The face is not a physical description — not eyes, nose, or mouth. It is the immediate presence of another person who resists being reduced to an object or idea.

When we encounter the face of the other, we are silently commanded: “Do not kill.” This command is not negotiated, not reasoned, not chosen. Responsibility arises involuntarily. The other’s vulnerability places an infinite demand upon us.

“The face speaks.”

Infinite Responsibility

Levinas’s ethics is unsettling because it has no limit. Responsibility is asymmetrical: I am responsible for the other regardless of whether they are responsible for me. Justice, reciprocity, and rights come later — ethics begins with excess.

This does not mean sentimental altruism. It means acknowledging that moral life cannot be fully justified or balanced. To be human is to be exposed, obligated, and never fully innocent.

“I am responsible for the other without waiting for reciprocity.”

Judaism, Scripture, and Philosophy

Although Levinas worked within the philosophical tradition, his thought is deeply informed by Jewish ethics and scripture. He wrote extensively on the Talmud, seeing in it a tradition of interpretation that privileges responsibility over doctrine.

For Levinas, revelation does not provide metaphysical knowledge. It sharpens ethical sensitivity. God is encountered not through speculation, but through the demand issued by the other person. Transcendence happens in ethical relation.

“The relation with the Other is a relation with mystery.”

Politics, Justice, and the Third

Levinas did not ignore politics, but he treated it cautiously. Once a third person enters the ethical relation, questions of justice, law, and institutions arise. Ethics must be translated into systems — yet something is always lost in the process.

Political structures are necessary, but they must never forget that they originate in concrete responsibility to singular human beings. When systems override faces, violence follows.

Legacy — Philosophy After Responsibility

Levinas transformed moral philosophy, phenomenology, theology, and political theory. He influenced thinkers across traditions — Derrida, Ricoeur, Butler, and many others — precisely because his thought resists closure.

His legacy is demanding and uncomfortable. Levinas offers no refuge in neutrality, no escape into systems. To think, after Levinas, is to accept that philosophy begins not with wonder, but with obligation.

“To recognize the Other is to give.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia