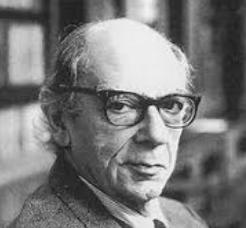

Isaiah Berlin — The Philosopher of Liberty, Pluralism, and Tragic Choice (1909–1997)

Isaiah Berlin was the great anti-utopian of modern political thought — a defender of liberty who distrusted every theory that promised final harmony. Against systems that claimed to reveal history’s destination or morality’s single true form, Berlin insisted on an unsettling truth: human values are many, often incompatible, and sometimes irreconcilable. Politics, for him, is not the art of perfection, but the art of damage control.

From Revolution to Liberal Skepticism

Born in Riga and raised partly in Petrograd, Berlin witnessed the Russian Revolution as a child. He saw at close range what happens when grand theories collide with stubborn human reality. The experience left him permanently wary of political salvation narratives.

After emigrating to Britain, Berlin was educated at Oxford, where he would later become one of its most celebrated intellectual figures. He moved easily between philosophy, history, and political theory, preferring essays and portraits to formal systems.

Ideas, for Berlin, were living forces with real casualties.

“Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made.”

Two Concepts of Liberty

Berlin’s most famous contribution is his distinction between negative and positive liberty. Negative liberty means freedom from interference — the absence of obstacles, coercion, and domination.

Positive liberty means being one’s own master — self-rule, self-realization, and collective self-direction. Taken in moderate form, this ideal is harmless. Taken as a political mandate, Berlin warned, it can become dangerous.

When rulers claim to know people’s “true interests” better than they do themselves, coercion can be justified as liberation. History, Berlin argued, is crowded with tyrannies born from this logic.

“Freedom for the wolves has often meant death to the sheep.”

Value Pluralism — Many Goods, No Final Harmony

At the heart of Berlin’s thought lies value pluralism. Human values, he argued, are objectively real but not reducible to a single scale. Liberty, equality, justice, mercy, loyalty, creativity — all are genuine goods.

The trouble is that they frequently collide. Increasing equality may restrict liberty. Loyalty may conflict with justice. Compassion may undermine fairness.

No master formula can resolve these conflicts in advance. Moral life involves tragic choices, not technical solutions.

“The possibility of conflict between values is the essence of what they are and what we are.”

Against Monism and Historical Destiny

Berlin opposed what he called monism — the belief that all true values must ultimately fit into one coherent system. Monism, he argued, fuels ideologies that seek final answers.

Whether in Marxist historical necessity, religious teleology, or technocratic planning, the promise is always the same: once the right theory is found, conflict will end.

Berlin thought this dream both false and dangerous. Conflict is not a temporary defect in human life. It is permanent.

“Total liberty for wolves is death to the lambs.”

The Hedgehog and the Fox

In one of his most famous essays, Berlin divided thinkers into hedgehogs and foxes. The hedgehog knows one big thing — a single organizing principle that explains everything.

The fox knows many things — multiple, sometimes inconsistent insights about the world. Berlin’s sympathies lay with the foxes.

Reality, he believed, is too plural, too resistant, too unruly to be captured by any single idea.

Liberalism Without Illusions

Berlin defended liberalism not because it perfects humanity, but because it limits cruelty. Liberal institutions create space for difference, compromise, and peaceful disagreement.

They do not guarantee virtue. They merely reduce the scale of disaster.

This modesty was deliberate. Berlin thought political humility was a moral achievement.

Legacy — Thinking Without Final Answers

Berlin left no grand system, only a constellation of arguments, warnings, and portraits. His work resists tidy summarization, because it resists tidy reality.

He reminds political philosophy that conflict is not a flaw to be engineered away, but a condition to be managed with restraint.

In a world hungry for certainties, Berlin’s pluralism remains an uncomfortable discipline — teaching that some losses are unavoidable, and some disagreements will never be resolved.

“The pursuit of perfection often leads to blood.”

CivilSimian.com created by AxiomaticPanic, CivilSimian, Kalokagathia